Photographs are manipulated daily by newspapers, bloggers and photographers. But when, if ever, should you make changes to an image?

Journalism is about packaging information into articles, or ‘stories’, that resonate with the readership.

Most of these stories come with illustrations in the form of photographs to help visualise the story, and just like the words you write, their production should always take into account ethical principles.

The American organisation National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) is the leading group of press photographers and has a code of ethics about visual manipulation, highlighting the importance of care when editing:

“Photographic and video images can reveal great truths, expose wrongdoing and neglect, inspire hope and understanding and connect people around the globe through the language of visual understanding.

Photographs can also cause great harm if they are callously intrusive or are manipulated.”

Correcting colour and brightness may seem normal, but sometimes journalist tweak images to make them more appealing or shocking. Cue the ethical alarm bells.

A key example of a photographic faux pas in action came when The Los Angeles Times published a front page that had been altered by the photographer Brian Walski.

The first two photos are the originals with the last being the blend of the two:

The blended image

It’s clear to see how the blended image conveys a radically different message to the events which actually happened, and incidentally, how this would change people’s perceptions of a story.

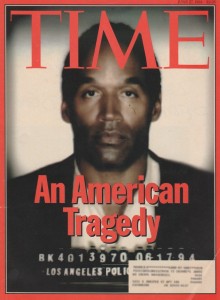

Similarly, when O.J. Simpson was tried and later acquitted of his ex-wife’s murder in 1994, Time was accused of digitally manipulating the image to make it darker.

Many said they’d made his skin colour darker than the other front pages on the newsstands.

Many said they’d made his skin colour darker than the other front pages on the newsstands.

It’s easy to argue that the text of an article may set right the wrongs of an edited photograph, but research shows that many readers focus heavily on photos, rather than the actual written article.

This lends to the notion that many readers will actually infer a great deal from photos, regardless of what you write to go around them.

The first step on the ladder for a reader to finish reading a story would be seeing an appealing image. Only then will they go to the headline, and then to the intro paragraph and the rest of article.

It’s a problem taken very seriously by the industry, and sadly one that’s rife across the globe. At this year’s World Press Photo Contest, around 20% of entrants were disqualified for significantly altering images and the first place winner was stripped of his prize in the wake of accusations of misrepresentation and image posing.

It’s not just a dilemma for national journalists though. The Associated Collegiate Press (the American version of the SPA) publish a Model Code of Ethics, with article 16 advising:

“Electronically altering the content of photos for news and general feature stories or as stand-alone news and feature photos is not allowed. Exceptions to this would be adjustments to contrast and similar technical enhancements that don’t affect the truthfulness of the subject and context of the subject or the scene.”

All in all, be mindful of the little changes you might make – and the impact they might have on the conclusions readers might draw from it.

Featured image used under Creative Commons Licence by epSos.de.